and the first uses of its fruit

The exact location from which the genetic ancestors of Coffea arabica began to spread across the world has not yet been definitely identified.

It can be assumed that the plant in its wild form was present in the area that is today northern Ethiopia and, perhaps, in the area of Arabian Peninsula known as Yemen, where different sources say it was cultivated for the first time.

in Arabia Felix

Before the eleventh century AD the coffee plant was found only in a few Ethiopian regions and in the mountainous areas in the south-west of the Arabian Peninsula. If on the one hand the title of ‘the cradle of the plant’ should go to Ethiopia, on the other the Arabs deserve recognition for its propagation and advancing its use as a beverage.

arrival of coffee in Europe

In the first half of the sixteenth century, the Ottomans conquered vast tracts of Arabia Felix and inherited the coffee tradition, leading to the development of cultivation on a larger scale. Within this period, the geography of the Yemenite territory underwent great changes and the areas dedicated to coffee crops expanded to meet a growing demand. Theories on the first forms of coffee roasting, similar to that of today’s, are dated to this period.

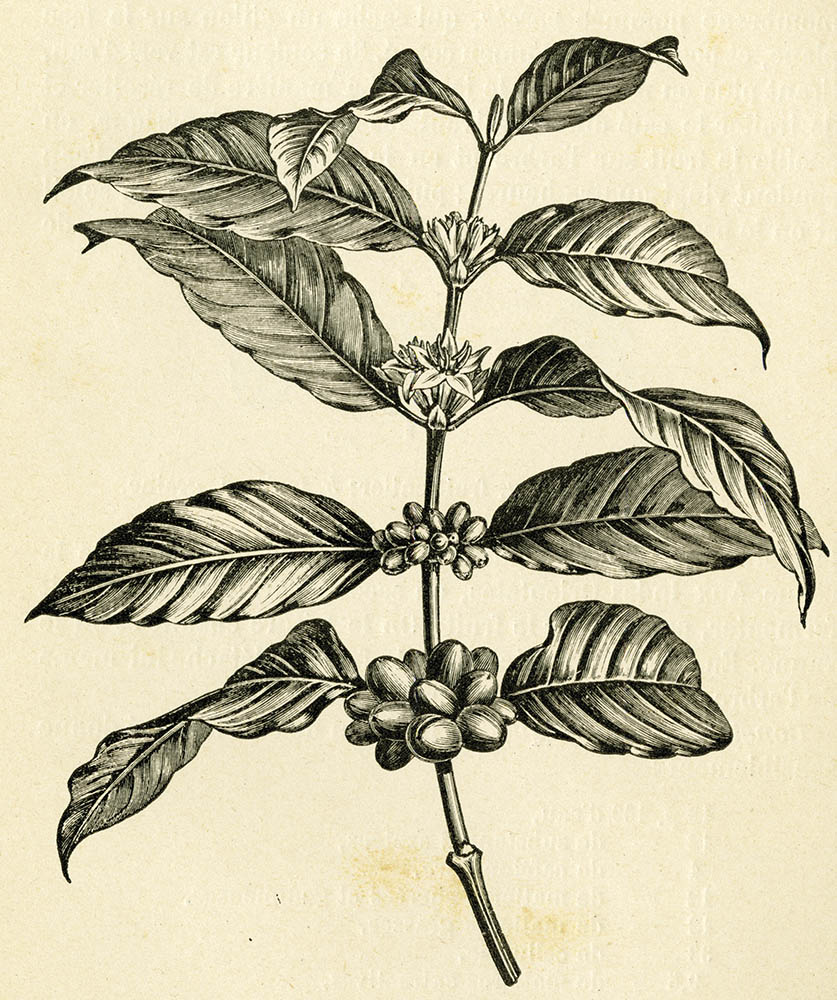

The plant was introduced to the European continent. The first experiments to acclimatise Coffea arabica to the botanical gardens of Amsterdam and the first attempts to transport and cultivate the plant in the Dutch colonies of Indonesia and Java date back to the period between 1615 and 1670. The early knowledge of the coffee plant was brought to the attention of Europeans mainly via travellers or merchants returning from the Near East and the Levant.

and the European conquerors

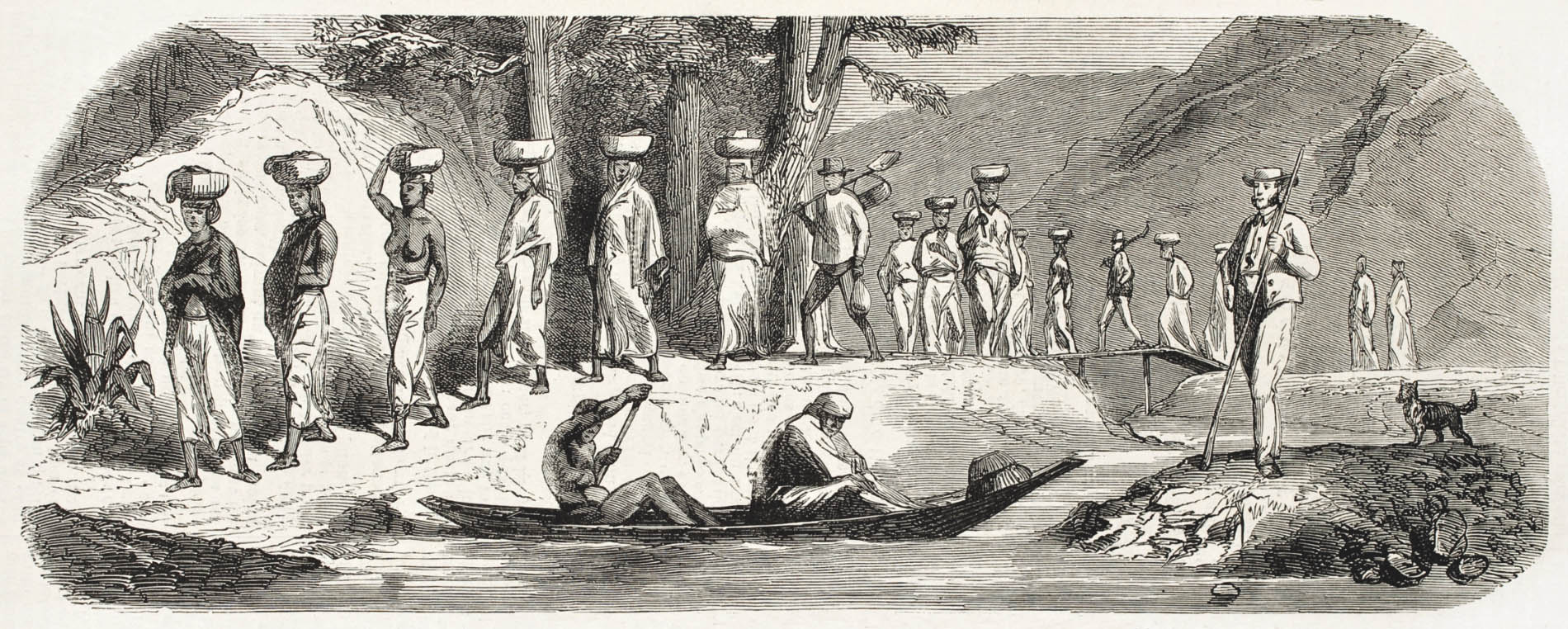

The Dutch East India Company was the great protagonist in the early history of coffee in the West. The Dutch began to cultivate the plant more intensively in their colonies during the second half of the 1600s, in response to growing demand for the beverage in Europe.

The mercantile spirit of this era, the development of trading companies and the first European stock exchanges advanced the exploitation of colonial resources and the subsequent consolidation of the Dutch East India Company as a major supplier. By the mid-eighteenth century, Holland was the largest supplier of coffee in Europe, even controlling its price per weight.

The Dutch East India Company exchanges coffee plants with numerous European botanical gardens. Some specimens are sent to King Louis XIV in 1714, triggering France’s involvement.

The first seeds of the plant arrive in Brazil, thanks to Portuguese merchants. Coffee cultivation in Brazil starts around the end of the 1720s using seeds stolen from Paris by Colonel Francisco de Melo Palheta.

The English introduce coffee cultivation to Jamaica on the hills of St Andrew, before extending it to the Blue Mountains.

For the first time, the Coffea arabica species is described by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707– 1778), who was also the first to catalogue it in the Rubiaceae family.

becomes global

By the mid-eighteenth century, coffee was being cultivated on five continents. In Asia, production remained in the hands of a few colonial countries, especially Holland and Britain, while other colonial powers began to move seriously towards Latin America.

The end of this era coincided with the abolition of slavery in the new nation states. Policies for keeping prices high opened up opportunities for cultivation in other areas: Mexico, Hawaii, Colombia, Venezuela, Puerto Rico, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Indonesia, El Salvador, Vietnam, Réunion and British Central Africa.

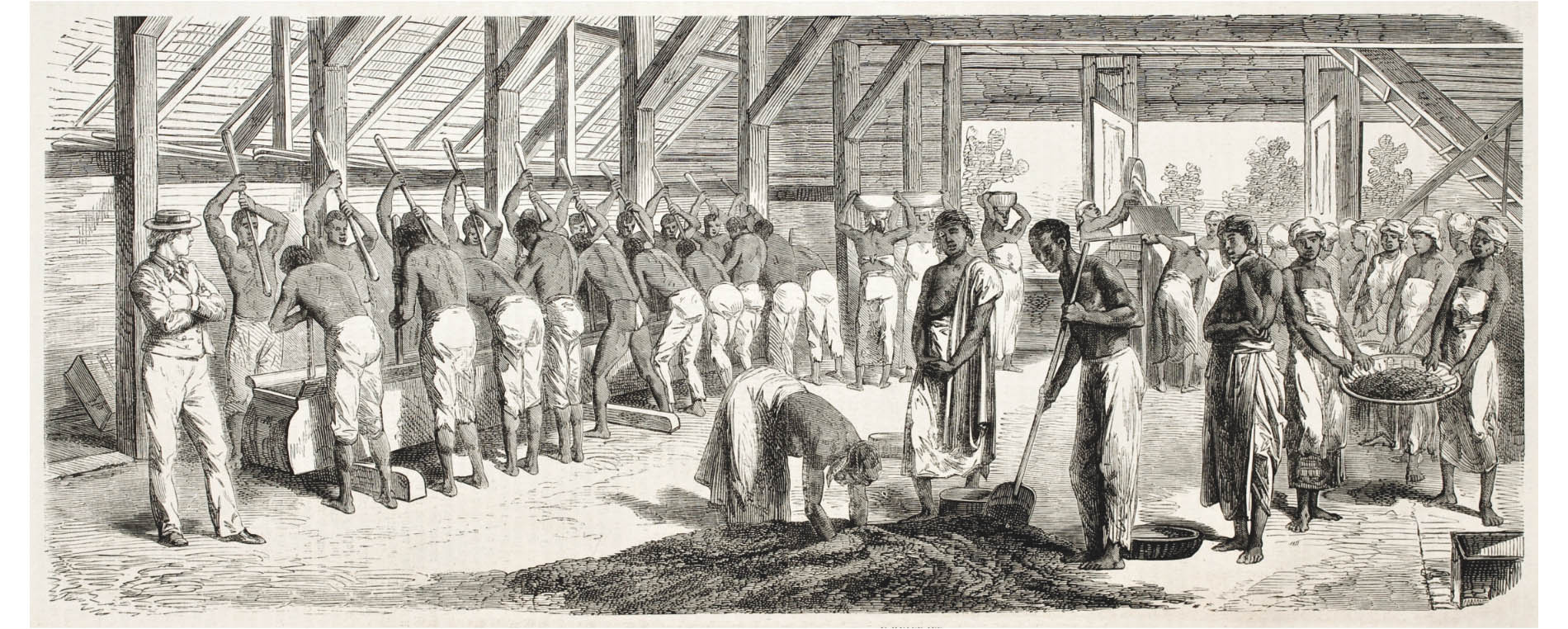

The Haiti Revolution saw indigenous slaves revolting against the harsh working conditions they endured on the coffee plantations under French and British rule.

Coffee rust (Hemileia vastatrix) appeared for the first time during an epidemic in South-East Asia, with devastating effects in various coffee-producing countries. It was a game changer in terms of coffee cultivation and globally shifted the focus away from varietal research towards disease resistance. This led to the introduction of various disease-resistant species, in particular C. canephora (Robusta), in many countries.

Coffee was consumed throughout Europe in the nineteenth century but supply was beginning to fall behind market demand. Brazil, ‘the sleeping giant’, was the perfect place to fulfil the need for expansion.

revolution and the evolution

of farming techniques

It was around this time that farmers all around the world gradually learned to use fertilisers and fungicides.

towards the free market

In Africa and other countries, the monopoly over coffee production and trade at the expense of local populations led to phenomenon of revolt and violence, ignited into full-blown civil wars in many countries, such as that which led to the coup d’état in Guatemala.

Following these events a series of agrarian reforms were implemented in many of the producing countries, favouring the formation worldwide of many associations, consortia and national and international bodies in general, to represent coffee producers and importers.

By introducing an innovative approach to agricultural production, through the use of genetically selected varieties, fertilisers and capital investment in more advanced technological equipment, most areas of the world saw a significant increase in agricultural production with the Green Revolution between 1940 and 1980.

Many nations responded to the growing demand for the beverage, especially in the United States, by embracing the promises of technology and the Green Revolution through the increase of the areas under cultivation, the introduction of new varieties with higher yields, a growing contribution from chemicals or the implementation of new agricultural practices and new technologies.

The 1990s were marked by a crisis in African production, especially early in the decade. This was then compensated for by considerable growth in some of the Asian states, primarily Vietnam, followed by Indonesia.

the era of sustainability

The main event in these years was the coffee crisis of the early 2000s, caused by excessive production in countries such as Brazil and Vietnam, combined with a high yield and sky-high costs. This crisis led to a price collapse with catastrophic results for many producers.

During this time, Brazil still dominated production, although Vietnam expanded considerably, leading it to be ranked second among the producing and exporting countries.